Why Do Our Waistlines Always Get Bigger in Middle Age? A Science Paper Reveals the Secret

A preclinical study from City of Hope Medical Center and UCLA has revealed the cellular culprits behind age-related belly fat, providing new insights into why our bellies widen with middle age. The finding also provides a new target for future therapies to prevent abdominal flab and extend healthy lifespan.

"As people age, they often lose muscle and gain body fat, even if their weight remains the same," said co-corresponding author Qiong (Annabel) Wang, PhD, associate professor of molecular and cellular endocrinology at the City of Hope Medical Center Diabetes and Metabolism Institute. "We found that aging triggers the arrival of a new type of adult stem cell and enhances the body's production of new fat cells, especially around the abdomen."

Working with co-senior author Xia Yang, PhD, and her team at UCLA, Wang and her team conducted a series of mouse experiments that were subsequently validated in human cells. Wang and her colleagues focused on white adipose tissue (WAT), the fat tissue that is responsible for age-related weight gain. While it's well known that fat cells get bigger with age, Yang and Wang hypothesized that white fat tissue also expands by creating new fat cells, meaning it may have unlimited growth potential.

To test their hypothesis, they focused on adipocyte progenitor cells (APCs), a population of stem cells in white fat tissue that give rise to fat cells. Wang's team first transplanted APCs from young and old mice into a second group of young mice. The APCs from old mice quickly produced large numbers of fat cells. However, when they transplanted APCs from young mice into old mice, the APCs did not produce many new fat cells. Their results confirmed that older APCs have the ability to independently make new fat cells, regardless of the age of their host.

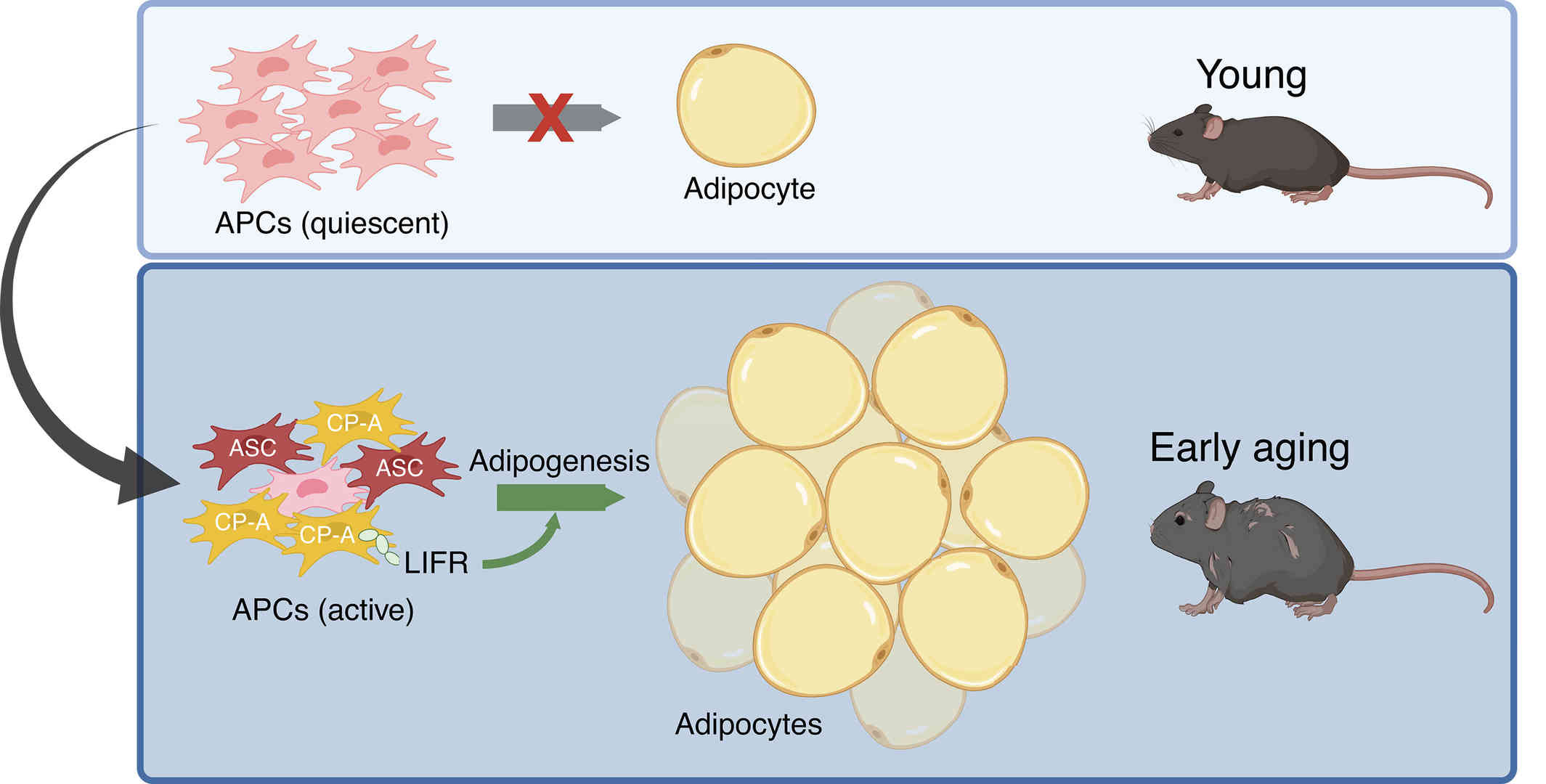

Fig. 1. Adipogenesis contributes to age-related visceral adipose tissue accumulation (Wang,

Guan, et al. 2025).

Fig. 1. Adipogenesis contributes to age-related visceral adipose tissue accumulation (Wang,

Guan, et al. 2025).

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, they next compared gene activity in APCs from young and old mice. While APCs were barely active in young mice, they suddenly woke up in middle-aged mice and began to secrete new fat cells. "While the ability of most adult stem cells to grow diminishes with age, the opposite is true for APCs — aging unlocks the ability of these cells to evolve and spread," said Adolfo Garcia Ocana, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology at City of Hope Medical Center. "This is the first evidence that our bellies expand as we age due to the production of large numbers of new fat cells by APCs."

Aging also transforms APCs into a new type of stem cell called committed preadipocytes, age-enriched (CP-A). In middle age, CP-A cells actively generate new fat cells, explaining why older mice gain more weight. A signaling pathway called the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) was shown to be critical for promoting the proliferation and evolution of these CP-A cells into fat cells.

"We found that the body's adipogenesis process is driven by LIFR," Wang explained. "While young mice don't need this signal to generate fat, older mice do. Our study shows that LIFR plays a critical role in triggering CP-A cells to generate new adipocytes and expand abdominal fat in older mice."

Wang and her colleagues next performed single-cell RNA sequencing on samples from people of different ages in the lab. Again, the team found similar CP-A cells that increased in number in tissue from middle-aged people. Their findings also showed that CP-A cells in humans have a high capacity to create new adipocytes.

"Our findings highlight the importance of controlling the formation of new adipocytes to address age-related obesity," Wang said. "Understanding the role of CP-A cells in metabolic disorders and how these cells emerge during aging may provide new medical solutions to reduce abdominal fat and improve health and lifespan."

Future studies will focus on tracking CP-A cells in animal models, observing CP-A cells in humans and developing new strategies to eliminate or block these cells to prevent age-related fat gain. This study not only provides a new perspective for us to understand the mechanism of middle-aged obesity, but also provides a potential target for the development of treatments for age-related metabolic diseases. By targeting the LIFR signaling pathway or regulating the function of CP-A cells, perhaps in the future we can more effectively manage abdominal fat and delay aging-related health problems.

Reference

-

Wang, Guan, et al. "Distinct adipose progenitor cells emerging with age drive active adipogenesis." Science 388.6745 (2025): eadj0430.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *